Aldus Up´s EuRopean Item Core Set for Reading Surveys, published on the K-HUB in June 2022, is now being tested in pilot surveys. First insights were presented at this year’s Frankfurt Book Fair and the Italian Book Fair “Più libri più liberi” in Rome. In this article, we will discuss some basic figures available from Italy, Spain and Norway to further explore what we already can compare, how important it is to look closer into the details underneath – and how ERICS can help doing just that in the future.

By initiative of Luis González, Managing Director of FGSR (Fundación Germán Sánchez Ruipérez), Aldus Up had the opportunity to present the first outcomes and current efforts of the Working Group on Reading on the Guest of Honour Spain professional stage at the Frankfurt Book Fair on October 19th, 2022. Cristina Mussinelli (Italian Publishers Association – AIE), who collaborates at the management of the Observatory of Reading Habits in Italy, outlined the general framework of the Aldus Up network and its numerous activities. Christoph Bläsi, Professor of Book Studies at JGU (Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz), then lead through the “road so far”, explaining what ERICS is and why we need it. Kristenn Einarsson, former Managing Director of NPA (Norwegian Publishers’ Association), eventually rounded up the presentation by discussing a few selected results from the current Norwegian Reading Survey.

The role of ERICS to enhance the knowledge of reading habits in Europe was then discussed in early December in a session held at “Più libri, più liberi” Book Fair in Rome, organized by the Italian Publishers’ Association. In this session, host Piero Attanasio, head of public affairs at AIE, had invited Massimo Pronio (European Commission Representation in Italy), Enrico Turrin (Deputy Director of the Federation of European Publishers) and Luis González to speak about ‘Aldus Up: A turning point in the collection of data about reading in Europe (Un punto di svolta nella raccolta dei dati sulla lettura in Europa)’.

What is ERICS – and why do we need it?

Interested parties from cultural politics in European countries as well as from the European publishing industry have been complaining for a long time that the results of reading surveys in different countries, if they exist at all, are hardly comparable.

An explorative “survey on surveys” presented at Bologna Children Book Fair and published on the K-HUB in June 2021, highlighted the necessity of harmonizing surveys on (amongst other things) reading habits in different European countries. Building on this preliminary study, the Working Group on Reading (consisting of representatives from NPA, GSR Foundation and the Department of Book Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University) proposed, early this year, a unitary core set of items [2]. The basic idea: by implementing this core set into future national surveys the degree to which results can be aligned with those from other countries in Europe is to expand significantly

The preliminary study published in June 2021 allowed for a first overview on what kind of parameters are prevalent in some 20, currently hardly comparable national, regular surveys on reading behaviour (Fröhlich et al., 2021) [1]. This was the basis for the development of ERICS, the EuRopean Item Core Set for Reading Surveys, suggesting basic questions, in the language of empirical social research: items for a unified standard. As its´ name already indicates, ERICS should be perceived as only the basic core of any future survey. The aim is by no means to equip all national surveys with an identical questionnaire, but to expand and adjust existing surveys. That way, established surveys can simultaneously continue to follow the items they have been tracking already – in some cases for decades – and at the same time become fit to yield comparable data with respect to this core set of questions. Apart from the most central sociodemographic variables (such as age, gender and level of education), the proposed questions focus on the general and relative ‘popularity’ of the three formats printed book, e-book, and audiobook, by polling not only the general consumption of said formats but also the frequency at which this happens, the time invested to do so as well as the number of ‘units’, which is to say, the number of books read or audiobooks listened to.

What we already know (or think we know): some compared data in three countries

After having drawn up a suggestion for such core items, the next and consequential step is their implementation in surveys in European countries. To that end, the research office of the AIE (Italian Publishers’ Association), which has been managing the annual survey on the Italian book market, including also some figures on reading habits since 2017, has used the ERICS framework parallel to the items of its previous questionnaire in the summer of 2022. Further pilots for which (partial) implementation or interlocutions thereof are under way, are the Spanish Reading Survey (Barometro de Hábitos de Lectura y Compra de Libros en España) [3.1], brought forward by the FGEE (Spanish Publishers’ Association) and the Reading Survey fostered by the Norwegian Publishers’ and Booksellers’ Association (Leserundersøkelse) [3.2].

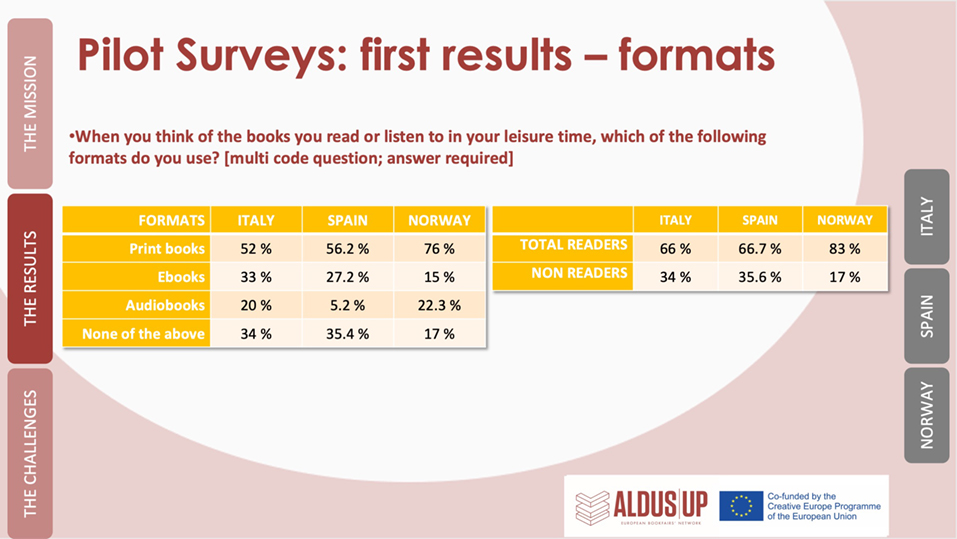

Some data from these three surveys can already be compared. They tell us, for example, that the share of leisure time book readers among the population is quite similar in Spain (67%)* and Italy (66%). Nonetheless, there are quite distinct patterns to be observed regarding the medium (format) which is used for these reading activities. And for both countries, there is a ‘slope’ in these average shares to be observed across the demographic spectrum, where young adults are more interested in reading than seniors, and in both countries, every second of said seniors is a reader (50% of above 64 year olds in Spain, 51% of above 74 year olds in Italy). But still, the graphs for both countries look very different. In Spain, the age groups between 25 to 59 years show a relatively even share of readers (around 67%), rendering the graph into a broad, central plateau with two inverse little ‘wings’ at both ends (upward for the 14-24 year olds and downward for the seniors). The Italian graph, on the other hand, appears more classical, starting with a remarkable 90% among the 16-24 year olds, and decreasing more or less gradually with each group to reach its lowest point in the upper age spectrum. In Norway, the situation is very much the opposite. Here, the share of leisure time readers is significantly higher, yielding a total average of 83%. And it is the seniors boosting this total upward, not the young adults. What we see is a steady increase from 77% among the young adults (16-19 years) to 89% among those aged over 69. Secondly, audiobooks (used by 23% of the population) are today more popular than e-books (15%) in Norway, whereas in Italy, the use of audiobooks is similarly widespread (20%) but e-books are much more popular (33%). In Spain, e-book use ranges ‘somewhere in between’ the aforesaid Italian and Norwegian values (27%), while audiobooks seem, so far, to be of very little interest (5%).

Problem: when average kills the insight

So especially the example of Spain and Italy shows that similar numbers of readers on the surface can indeed be the result of averaging quite different situations underneath. The actual insight is thus hardly found in the total average but rather in the subsets. Accordingly, the low number of non-readers in Norway (17%) might give the impression that there is no need to worry about the future of book reading. But this would mean to ignore the fact that this above average popularity of books (seen from a pan-European perspective) is in reality in decline in the younger generations – so even if it does not decrease further for future generations, the total average across all age groups will still go down in years to come.

The underlying reasons for the individual statistical phenomena, more so, the consequences stakeholders both in the book market as well as on the political stage should derive from those numbers, were in the spotlight in our presentations both in Rome and Jakarta (see previous article [4]). But more plainly speaking, it needs to be pointed out that at the moment, we only have very limited access to such directly comparable figures. Already the heterogeneously chosen intervals of age groups, which went uncommented in the text above, give a basic idea of how quickly the vision can be blurred when trying to discern the details. Even though precise data may exist, the angle through which it is displayed in the final presentations always means a reduction.

More challenges for ERICS and the evaluation processes behind it

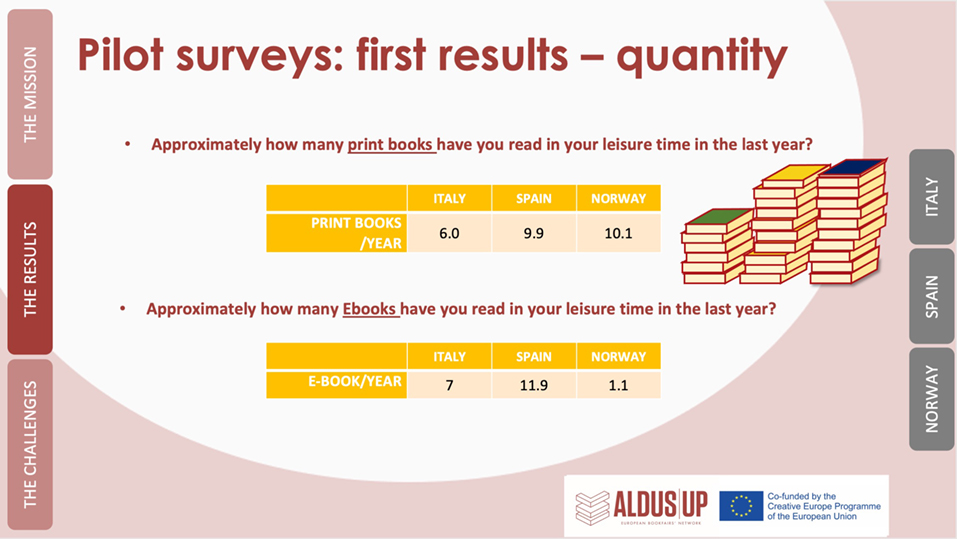

At first inspection, the three angles suggested by ERICS – How often do you read? How much time do you spend doing so? And how many books do you read? – may seem like different approaches to the same question: ‘How much do you read?’ But they are not the same. For example, the results in the Italian survey tell us, as mentioned above, that there are more people using e-books than audiobooks. But approaching a ranking among the three formats based on the time which users spent on them in the past week, within the very same sample, leaves us with an inverted result. Suddenly, printed books are ‘least popular’ and audiobooks win the palm. We cannot yet say whether the same thing is the case in the Spanish or Norwegian sample, at least not based on how the results are currently presented.

Also, the number of units consumed per annum in each country is somewhat nebulous, since all three surveys do give us statements on this issue, but each refers to different subsets of their respondents, and it is not always obvious which one that is. As for the frequency at which readers use their preferred formats (if this parameter is part of the questionnaire at all), differing intervals are offered as options for the respondents. This means that the data is already blurred in the collection (whereas the age is usually collected in exact numbers and grouped only afterwards). And even if all these numbers were already comparable – if the only book you read in 2022 were Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and your best friend read three Agatha Christie novels, which of you read ‘more’? And did you possibly read just a few pages every other day, or tackle all four volumes during your Christmas vacation?

Get the right data – and get it as directly as possible

So the challenge is at least two-fold: on the one hand, there is the issue of (non-) comparability caused by the various kinds of data that is already out there, trying to get seemingly similar answers by asking very different questions. To tackle this, using a common set of items, like ERICS, is quite a straight-forward solution on offer. On the other hand, in some cases, comparable data is already out there, but we can, more often than not, only see it through a frosted glass panel. Ploughing through the results and identifying commonalities is cumbersome, to say the least. Candidly speaking: a work that is cumbersome requires time, which equals money, which is obviously the central delimiting factor when it comes to finding someone (be that a person or an institution) willing to do so. What we propose here is a sort of “upstream ERICS-ification”: the more data is collected directly with the items that are interesting for a comparison, the easier and less error-prone are the “downstream” processes. Apart from the different survey designs and equally diverse choices how to present results to the public, there is yet another factor rendering comparisons difficult: the fact that results are, so far, collected and regarded from a national rather than international perspective manifests in the predominant habit of publishing those results (only) in the respective national language. Needless to say that this adds up all the more to the required time budget. So we are happy to say that our work has an unforeseen but very beneficiary side-effect, namely that by engaging with survey makers, we are also promoting this European perspective and making some of the results, for the first time ever, available also in English.

Where do we go from here?

In the long run, our – ambitious – goal is quite simply put: establishing ERICS as a common standard and one day have (a core set of) comparable data across all of Europe, collected through the national surveys. In the medium run, this means we are now hoping to find more partners interested to implement ERICS and enlarge the number of countries for which comparable data is available – the IPA congress in Jakarta is only one example of our efforts to get the discussion going [4]. And this means, for the ‘short run’, in the past weeks we have been looking very thoroughly into the results in our pilots, to a) report back to our partnering survey makers what they could or should adapt to make comparison easier, but also b) find inspiration in those individual solutions to improve ERICS, assessing how both the collection and presentation of data can be optimized in the future.

Already, we have had the opportunity to discuss some of those findings with the makers of the Spanish survey, and are thus quite excitedly looking forward to the beginning of 2023, when the results of the next Barómetro de Lectura y Compra de Libros will be made available. In the mean time, make sure to stay tuned to the KHUB to read our upcoming posts, in which we will share with you in more detail what we could, so far, find out about our central reading variables in our three pilot countries: How often do readers find the time to sit down and read (or listen to) a good book? How much time do they spend doing this in their average week? And through how many books do they get over the course of one year?

* We used the numbers given in the official presentation of the Barómetro results in Frankfurt. These did not include comic books and graphic novels in the numbers for book reading. For the presentation in Rome and in this article, we used the numbers adjusted to include also comic books, which leads to 66.7% instead of the earlier 64.6%. Another important detail is that in those total averages, audiobook users are included in the Italian and Norwegian Survey, but not the Spanish Survey.

By

By